We’ve had a lot of great feedback on registers, but by far the most common reaction is a sense of puzzlement over how simple they are, and how minimal the data in each register is.

Registers are minimal by design, as set out in the characteristics of a register:

| “2. A register only holds the data it was created to record, and nothing else. It never duplicates data held in other registers. Registers link to data in other registers to avoid the need for any duplication.” |

Registers record the way things are

The primary stakeholder of a register is the custodian, the person responsible for keeping and maintaining a list of the things they manage.

Tony Worron, our first custodian, immediately saw how operating a register would help people use the correct names for countries but like Stephen McAllister, the custodian of the Local Authority, England alpha, was uncomfortable recording data for which his organisation was not responsible.

This is both a natural and understandable reaction to being a custodian. Each register must be managed by a custodian who has an authority over that data, not just a copy of it. For a register to be viable it has to be trustworthy, and it’s the authority of the custodian, both in terms of domain expertise, and being responsible for managing the things recorded in their register, which creates the trust essential to help us get from data to registers.

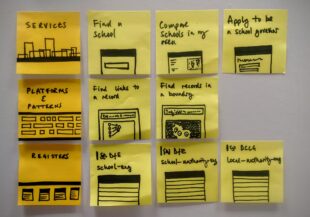

Services change quickly to meet user needs

Services help users to perform an action and it’s the role of a service to present the right data to the right users at the right time. Registers provide the data but it's services that put it into the context of users.

For example, a service that asks a user their country of origin only needs countries which are current; but a service asking in what country a company was founded may need names of countries which no longer exist; and a service may also need the territory register to help a user find the right trade-tariff.

Patterns and platforms emerge from services

When services start to repeat the same task, the cross-government design team identify and use the duplication to establish service patterns and standards and design patterns.

A design pattern may need an index, by which we mean a copy of some of the data held in a register formatted for quick access in a service. A need we have identified through working with service teams is for a platform with common indexes allowing services to search across registers for text and links and filter the results by geography and time.

Generic search indexes will help service teams use registers in many cases, but some services will also need indexes which are more specific to a single design pattern. For example, a form allowing a user to select a worldwide location using autocomplete may also need to include synonyms, endonyms and common typos of country names to help users find a register entry.

Platforms enable people to work on data from other people’s registers, and break down the silos often found within a single organisation. They help separate the concerns of keeping and maintaining data from the separate concerns arising from finding the right data and presenting it to users. For example, many services that depend on address data provided by users would benefit from good quality address matching. An easy-to-use address index would be of huge benefit to these services. ONS, who have great expertise in processing informal text with data, are extremely well placed to provide such an index to the rest of government.

Towards a digital ecosystem

We haven’t described these layers of registers, platforms and services as an architecture because it’s not a solid, centrally controlled structure. Strictly speaking, services don’t need platforms and platforms don’t need registers, but the absence of platforms make services more expensive to develop and harder for teams to change. The absence of registers has made government data harder to trust between organisations, with multiple copies of the same data being maintained across government.

We want to enable anyone to build on open registers, both inside and outside of government.

Many government service teams already use platforms built by teams outside government and we're looking to open up the platforms we have built.

Which is why we call this an ecosystem, with each layer containing different people with different concerns, working at different paces.

A service evolves as it learns more about the needs of its users. Service managers are responsible for the service and their teams are the primary users of platforms. The teams operating platforms need to learn from services and evolve their platforms in ways which don't break the services built upon them. Underneath all of this are registers, looked after by custodians who need to respond to changes in legislation.

A vibrant ecosystem delivers benefits for all stakeholders, as Simon Wardley alluded to in an old blog post.

As for registers, it’s the role of the custodian of the field register and the register register, the Registers Design Authority, to help government establish registers, and provides stewardship to ensure they meet the needs of a digital ecosystem.

Pace layering, inspired by Stewart Brand’s The Clock of the Long Now.

Recent Comments